The Union's Weapon: The Telegraph

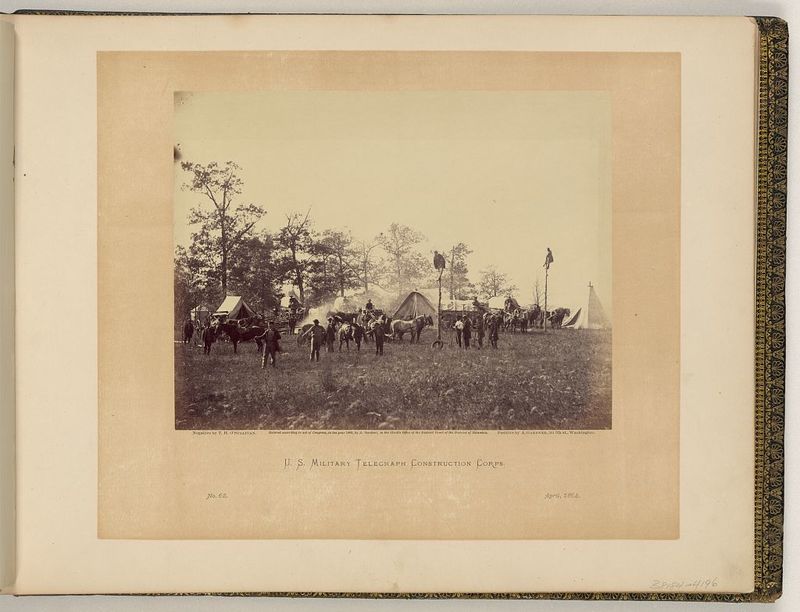

The telegraph transformed communication during the Civil War. In the past, communication had been problematic as connecting with individuals was difficult and time-consuming, and the military’s system of communication was becoming ineffective and needed improvements. According to David Bates, “The U.S. Signal Corps' system—flags by day and torches by night—stood inadequate to the vast terrain and the huge, dispersed forces engaged in the struggle” (x). However, in 1844, communication was forever transformed when “Samuel F.B. Morse [created] the first telegraph” (Botjer). This invention improved communication, and it served as a point of connection in the war. In order to maintain and expand these connections, the United States Military Telegraph Corps (USMT) started hanging telegraph lines for the Union. In the photograph, “U.S. Military telegraph construction corps/negative” (1864), Timothy O’Sullivan shows a group of USMT workers operating in an area possibly in Virginia. The effectiveness of the USMT allowed the Union to exchange messages quickly through the telegraph. In fact, George Botjer claims that “the Morse telegraph reduced the travel time of information from days, weeks and months to seconds and minutes.” Communication was broadcasted quickly across large areas connected by new telegraph lines. In addition, the efficiency of the USMT helped transform the usage of the telegraph poles and advance Civil War. These poles were soon needed on the frontlines during the war, and the USMT workers used the telegraph poles to create mobile communications for the Union. According to Bates, “Portable, frontline electric communication for field operations [were now] required” (xi). As a result, the USMT had to be efficient when setting up telegraph poles on the frontline of the Union’s battles. The efficiency of the USMT built confidence in the Union, and the spread of the telegraph helped the Union win battles and advance the Civil War.

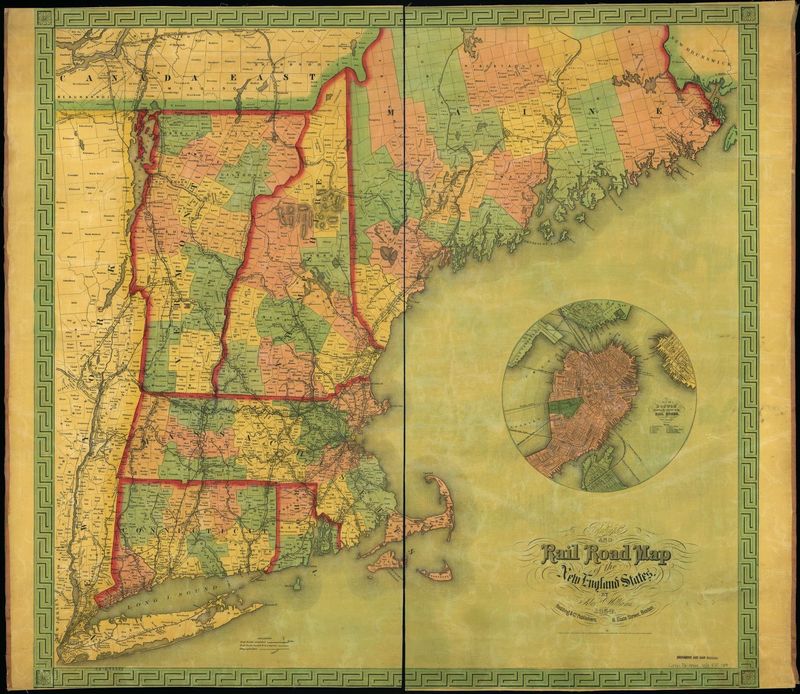

Although the telegraph was first introduced in 1844, the usage of this technology quickly expanded throughout the Civil War. Alexander Williams records the expansion of the telegraph and railroads in his map called the “Telegraph and Rail Road map of the New England States” (1854). The map shows how the Union embraced the telegraph and was its prime beneficiary. According to Hal Wallace and Connie Holland, “By 1865 about fifteen thousand miles of military telegraph wire had been erected by the Union, and only about a thousand miles by the Confederacy” (168). The Confederacy was at a disadvantage since it could not remain connected as easily as the Union. In addition, the Confederacy fought a defensive battle on its’ own territory where the telegraph was not beneficial. Meanwhile, the Union utilized the telegraph to improve strategic planning and advance the Civil War. According to David Bates, “Lincoln was the first president and commander in chief to be able to be in almost instant touch with armies in distant fields of war” (ix). The telegraph allowed Lincoln to remain connected with his army, and Lincoln was able to better plan and communicate with his army general Ulysses S. Grant. In addition, the reliability of the telegraph created peace for the Union. According to Bates, “the electric telegraph maintained speedy, almost instantaneous communication between Washington and armies in distant fields” (x). This provided peace because the army was able to remain connected with Lincoln and people back home. Lincoln experienced this peace when writing the emancipation proclamation in the War Department Telegraph Office. According to Bates, “[Lincoln] said he had been able to work at [Major Thomas Eckert’s] desk more quietly and command his thoughts better than at the White House, where he was frequently interrupted” (141). This seems contradicting as the war office might be perceived as noisier than the White House; however, the telegraph produces a peaceful environment for Lincoln. Although the telegraph was mostly successful, the ineffective uses of the telegraph foreshadow the ending to the war. For example, Lincoln telegraphed the union army to destroy the rebels after he had announced his compensated emancipation plan. Unfortunately, Lee’s army escaped, and Lincoln felt pressured to establish his emancipation proclamation (Bates 142). If the telegraph had been received, Lincoln might not have established his emancipation proclamation, and the US would remain in conflict. As it is seen on William's map, the telegraph expanded alongside the railroad.

Works Cited

Bates, David Homer. Lincoln in the Telegraph Office : Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps During the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press, 1995. EBSCOhost, proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=44434&site=eds-live.

Botjer, George F. Samuel F. B. Morse and the Dawn of the Age of Electricity. Lexington Books, 2015. EBSCOhost, proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1063855&site=eds-live.

Neil Kagan and Stephen G. Hyslop. Smithsonian Civil War: Inside the National Collection. Hal Wallace and Connie Holland, Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Books, 2013.

Appendix A

O'Sullivan, Timothy H, and Alexander Gardner, photographer. U.S. Military telegraph construction corps / negative by T.H. O'Sullivan, positive by A. Gardner. 1864 Apr. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2007682521/>.

Williams, Alexander. Telegraph and Rail Road map of the New England States. Boston, 1854. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/98688383/>.