The Culture of Property

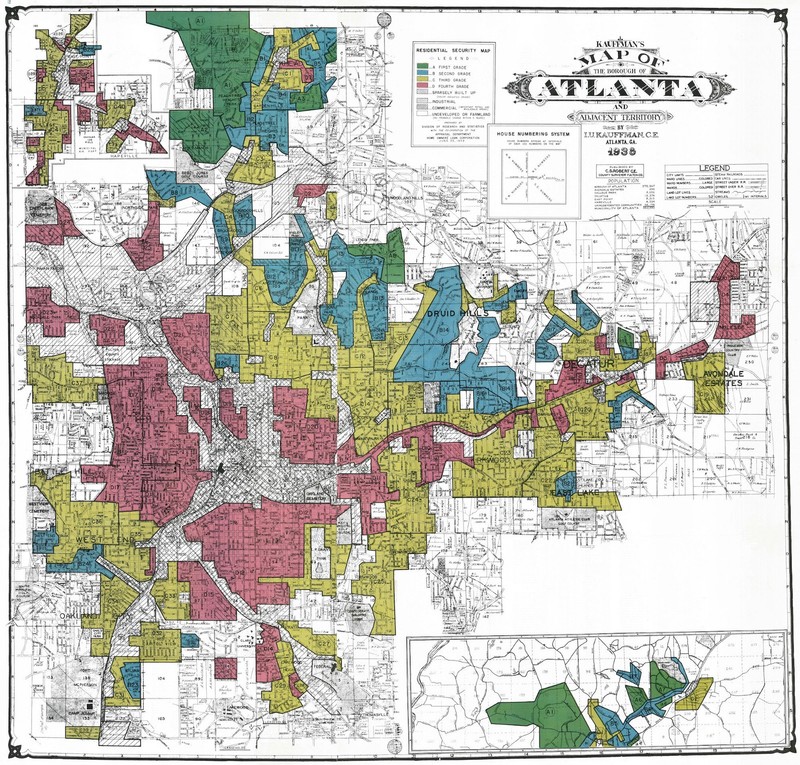

Atlanta was not always spatially divided by race and class. In the 1880’s and 1890’s real estate dealers capitalized on the high migration and developers built rental housing throughout the city. The culture was not yet concerned about racial segregation and resulted in a city mixed in class and race. Between 1910 and 1933, owning housing became higher status symbol due to work to elevate it by the government (Varaday). By the 1950’s the city evolved into one marked by extreme concentrations of poverty and racial and class exclusion. The FHA showed its racialized view of property by recommending that subdivisions should accept the covenant to allow specific race to live there. Developers accepted the covenant in order to meet the FHA standards. During the 1920’s, Atlanta’s white elite promoted segregation through restrictive covenants, ordinances, and zoning plans (Varaday).

Housing competition became extreme in the 1940’s as black families expanded into the mixed-race west side of the city. Eventually, in 1948, they moved westward into white neighborhoods. White residents threatened the black residents, but they refused to move. To mediate the differenced the biracial West Side Mutual Development Committee was created to mediate housing issues between blacks and whites. Black housing was developed in “Proposed Expansion Areas”, but it failed to calm protestors. From 1922-1950, Atlanta’s formerly mixed-race layout transformed into housing blocks that targeted specific racial groups. The spatial area available to blacks remained tightly constrained while white families continued to expand into suburban areas. The Federal Housing Administration made it notoriously difficult for African Americans to settle in suburbs because they would not insure African American’s home loans. In 1949, blacks were one-third of the city’s population, however, they only occupied one-fifth of the city’s land (Lands 196). By 1960, it was publicly acknowledged that I-20 west was established, in part, to serve as a boundary between white and black communities. Local black residents and leaders refused to accept white claims to specific neighborhoods.

The post-1990’s immigrant flux overcame the last of the resistance. Since 2000, Cobb County has increased immigrant population by 45% and Gwinnett County has increased by 72% (Lands 207). Also, Metro Atlanta had the largest gain of African American population of any metro area from 1990-2004 (Lands 207).

Works Cited

Lands, Leeann. The Culture of Property: Race, Class, and Housing Landscapes in Atlanta 1880-1950. The University of Georgia Press, 2009.

Varady, David P. “American Residential Segregation.” Journal of Urban History, vol. 43, no. 1, 22 Nov. 2016, pp. 166–171., doi:10.1177/0096144216680248.